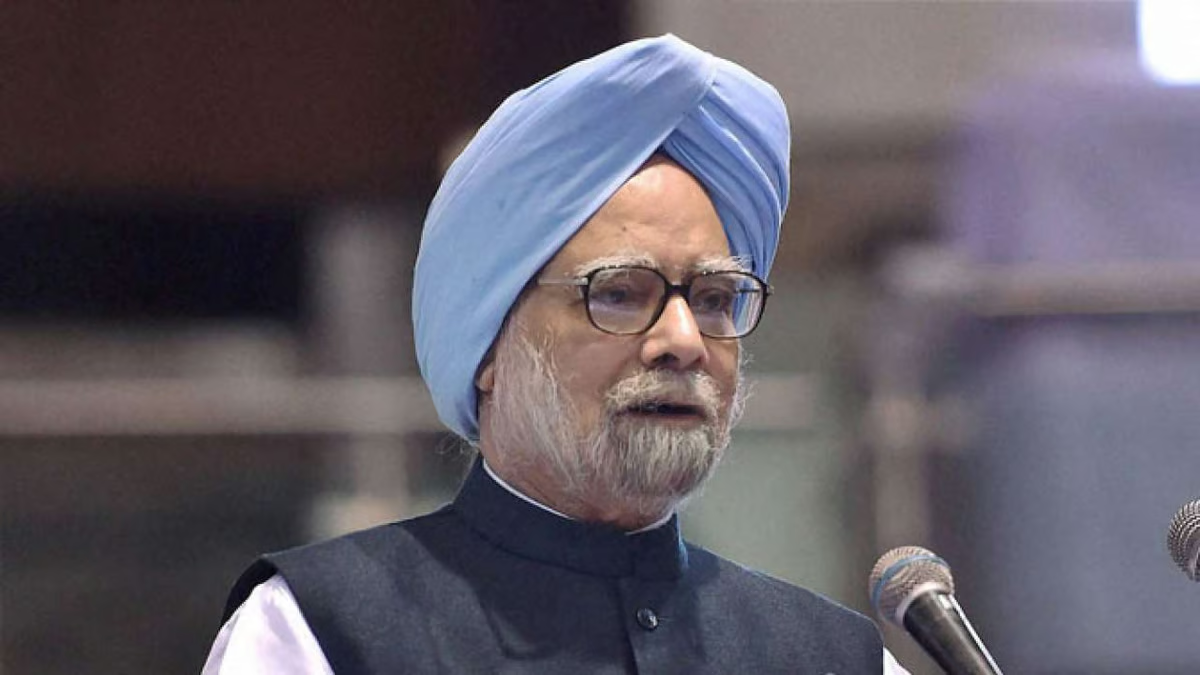

The former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who passed away recently, scripted India’s belated economic reforms, chiefly liberalization and globalization, as Finance Minister under the active encouragement of then-Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao. Singh was well-read, well-qualified, suave, humble, and accessible, wearing many hats, including Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. The notorious license raj, which held sway from independence until Rao took the reins, stifled the entrepreneurial spirit of Indians, condemning them to shoddy goods and services. Scooter drivers, for instance, negotiated bends with their hands flailing pathetically in the absence of indicators. For these drivers and their wives nervously clinging to their infants, foreign collaboration was manna from heaven, bringing safety features and better mileage. What the Rao-Singh duo achieved was not earth-shaking, as they primarily plucked low-hanging fruits, yet they earned the nation’s gratitude for their efforts.

However, unshackling industry alone was insufficient. The share of manufacturing in the nation’s GDP continues to languish at a dismal 15% in 2024, with agriculture tottering at 16%. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) initially filled gaps in sectors like white goods and automobiles but failed to transform the manufacturing landscape. Globalization, the second leg of the reforms, led to unbridled imports, resulting in a deluge of cheap Chinese goods in Indian markets. Despite initiatives like “Make in India,” manufacturing remains an unfulfilled promise. For instance, mobile handsets “made in India” is often an empty boast, with iconic foreign brands using the country merely as an assembly base. In the sensitive defense sector, foreign arms majors are reluctant to share their technology. Multinational corporations, more interested in exports than in setting up manufacturing facilities, have further hindered progress. Even under the Narendra Modi regime, this trend persists, with Tesla preferring to export from its facilities in China and California rather than manufacture in India.

The duo also failed to curb electronic imports, overlooking the necessity of a state-of-the-art domestic semiconductor industry, crucial for comprehensive economic development and reducing foreign exchange outflows. India’s economic progression remains lopsided, with services leapfrogging ahead of farming and manufacturing prematurely. In 2024, services contributed 60% to GDP, continuing a skewed growth story. IIT-educated engineers often prefer the comfort of air-conditioned offices in banks and service providers over working in factories, exacerbating an internal brain drain. The Rao-Singh duo did not address this imbalance with the seriousness it deserved.

Economists had hoped for FDI-led manufacturing growth, but instead, the nation received Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI), which neither boosts employment opportunities nor enhances the production of quality goods. FPI’s volatility makes the stock market risky, with capital moving in and out at will, unchecked by exit taxes or minimum investment duration requirements. This has rendered Indian bourses hostage to liquidity-driven booms and busts. Furthermore, FPI’s focus on Sensex stocks has led to inflated valuations unaligned with economic realities. Domestic crooks have exploited participatory notes to launder black money through round-tripping, where illicit funds are returned to India as legitimate investments, destabilizing the stock market and the broader economy. Singh’s faith in FPI overlooked its potential risks, including the distortion of corporate governance.

Ethically, Singh’s impeccable reputation was tarnished by his passive oversight during controversies like the 2G telecom license allocation and coal block allotments. The “first-come, first-served” process allowed non-telecom operators, such as fruit vendors, to secure licenses for profiteering. This led to the Supreme Court canceling 122 telecom licenses in February 2012 and 214 coal block allotments in 2014, emphasizing transparency and competitive bidding. Although the court did not name Singh directly, the verdicts signaled a failure of oversight.

Singh’s silence amid corruption scandals drew parallels with Bhishma from the Mahabharata, who, despite his virtues, remained a mute spectator during Draupadi’s disrobing. Holding the highest executive office demands action, not passive observation. Singh’s reluctance to confront political realities and corruption diluted his otherwise stellar contributions to India’s economic transformation. As an economist, he may have excelled, but as a politician, his inability to navigate the rough terrain of realpolitik left much to be desired.

S Murlidharan is a freelance columnist and writes on economics, business, legal and taxation issues