The Constitution of India envisages a harmonious relationship between the three branches of the state: the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary, each functioning within its constitutionally defined domain. The doctrine of separation of powers, accompanied by a system of checks and balances to maintain a harmonious interplay between the three state organs, is central to preserving democratic accountability and institutional integrity. However, many a time, the relationship between the legislature and judiciary has been marred by tensions and confrontations over constitutional interpretation, amendment powers, judicial independence, and institutional supremacy.

While Parliament is vested with the full power to enact legislation within the limits of the Constitution under Articles 245 to 255, the judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court (SC), also drives its authority to interpret legislation and enforce constitutional provisions under Articles 124 to 147. But many a time, the limits of legislative competence and the scope of judicial review have come into conflict, giving rise to controversies, contentious debates, and conflict over superior institutional authority. These conflicts often involve questions of parliamentary sovereignty versus judicial supremacy and the interpretation of constitutional provisions. The compelling question is: who is supreme in democracy?

The answer is, as former chief justice M.N. Venkatachaliah aptly observed, “It is imperative that both Parliament and judiciary must act as co-guardians of the Constitution, rather than adversaries seeking institutional supremacy.” But the ongoing contestation over the separation of powers and the limits of judicial review, especially when executive and legislative actions come under judicial scrutiny, reflects a dynamic constitutional dialogue. Several recent legislations, including the Farm Laws, Electoral Bonds Scheme, and the Waqf Amendment Act, have been subject to intense judicial scrutiny. The SC interventions in some of these cases have been labelled by the legislature as judicial overreach, thereby triggering a contentious debate over the legitimacy of judicial review in matters of public policy.

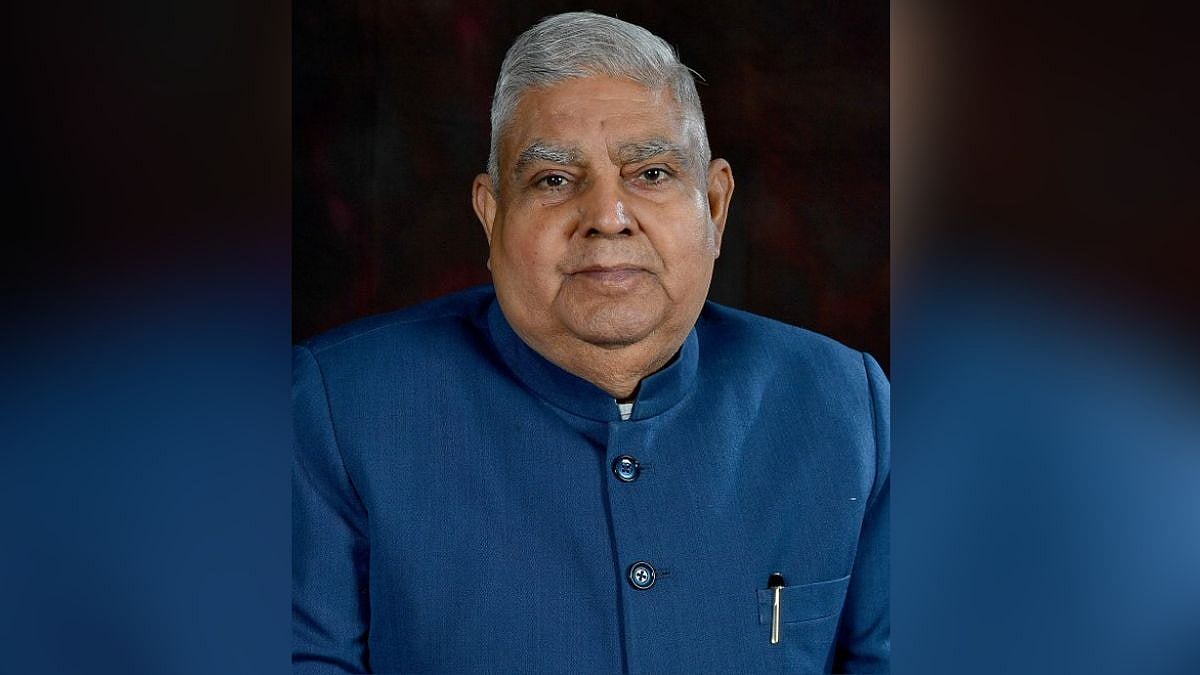

Take the case of Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar’s recent outburst against the judiciary, which has been seen as a concerted attack on judges and their powers and a gross violation of the responsibilities of the constitutional office he holds. In criticising the SC’s April 8 verdict in the Tamil Nadu vs Governor case, where the Court set a three-month timeline for the President to act on state bills forwarded by governors, the Vice President came heavily on the judiciary, saying judges are usurping the roles of the legislature and the executive. In his view, the judiciary cannot give directions to the President and act as a “super parliament”, overstepping its role. He went further in describing Article 142, based on which the SC prescribed a timeline for the President and governors to take a decision on bills, as a “nuclear missile against democratic forces”.

Warning against overlapping of powers among the three constitutional state branches, Dhankhar also said that the court has “absolutely no accountability because the law of the land does not apply to them”. It does not require political expertise to understand the motive behind the Vice President’s comments, as others—BJP MPs Nishikant Dubey and Dinesh Sharma—have taken a cue from him and criticised the court. Though BJP president J.P. Nadda distanced his party from the remarks of Dubey and Sharma, the fact remains that in showing disrespect to the court and not abiding by constitutional restraints, some elements in the BJP continue to question the judiciary, though in a constitutional system, with a variety of checks and balances, the judiciary is indeed the custodian of citizens’ fundamental rights and the Constitution’s letter and spirit.

The Vice-President and the two BJP MPs are under oath, which requires them to “bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution”. Article 142 is a part of the Constitution and criticising it in strong terms amounts to the violation of Dhankhar’s oath of office. As the chairman of the Rajya Sabha, Dhankhar is duty-bound to remain neutral with regards to the functioning of the different branches of the state. If Dhankhar has a problem with Article 142 and Article 145(3), which deal with the composition of SC benches that decide questions of law, Dubey and Sharma have found it difficult to accept the SC’s stand that certain aspects of the Waqf Act might be put on hold to ascertain their constitutional validity. The disdainful remarks of the two MPs against the SC and CJI Sanjiv Khanna not only show disrespect to the apex court but also amount to questioning its integrity.

In the past, Dhankhar had questioned the power of the Court to strike down laws passed by Parliament and cast doubts even on the basic structure of the Constitution. For instance, in October 2024, the Vice President, going beyond the remit of his office, had defiantly questioned the basic structure doctrine of the Constitution formulated by the 13-judge bench of the SC in its historic Kesavananda Bharti case in 1973. In this seminal case, the top court had ruled that Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution under Article 368 is not unfettered. The basic structure doctrine restricts Parliament from amending the Constitution in a manner that abrogates its fundamental framework, including rule of law, separation of powers, and judicial independence. The ruling was perceived by many within the legislature as judicial encroachment upon parliamentary sovereignty.

In questioning the well-settled judicially pronounced basic structure doctrine, Dhankhar implied the supremacy of Parliament over the judiciary. It is in this context his current criticisms of the apex court are being seen: an affirmation of his resolve to take on the judiciary, which violates his oath of office. While some, like independent Rajya Sabha MP Kapil Sibal and former justice Ajay Rastogi, have called Dhankhar’s remarks “unconstitutional and politically motivated” and defended the court, denying claims of judicial overreach, the discomfort in the ruling party over the SC’s ruling in the Tamil Nadu case is quite evident. Despite Nadda’s instruction to avoid targeting the judiciary, party leaders have continued to criticise the Supreme Court.

So, how does one see the current contestation between the legislature and the judiciary? The answer lies in the fact that both the institutions play important roles in the functioning of India’s constitutional democracy. The relationship between the two must be governed by mutual respect and a shared commitment to the Constitution as the ultimate sovereign.

The writer is a senior independent Mumbai-based journalist. He tweets at @ali_chougule