“Disability is just human diversity,” in a TEDx talk he delivered in 2022. “If opportunities are provided at the right time, if the support system is ensured, every individual – with or without disability – can perform.”

Despite losing most of his own vision at a very early age, cricket captivated Mahantesh’s imagination. He couldn’t watch it but the energy of his friends playing in the neighborhood was infectious, and the heavily accented cricket commentary he heard on the radio was strangely gripping. This began a childhood obsession with cricket that blossomed into a lifelong pursuit. If cricket provided him with an opportunity, it was his family that became the support system that egged him on to perform. He started by playing an improvised version of cricket with his mates at the blind school and his professors and eventually went on to become one of the pioneering blind cricketers of the country.

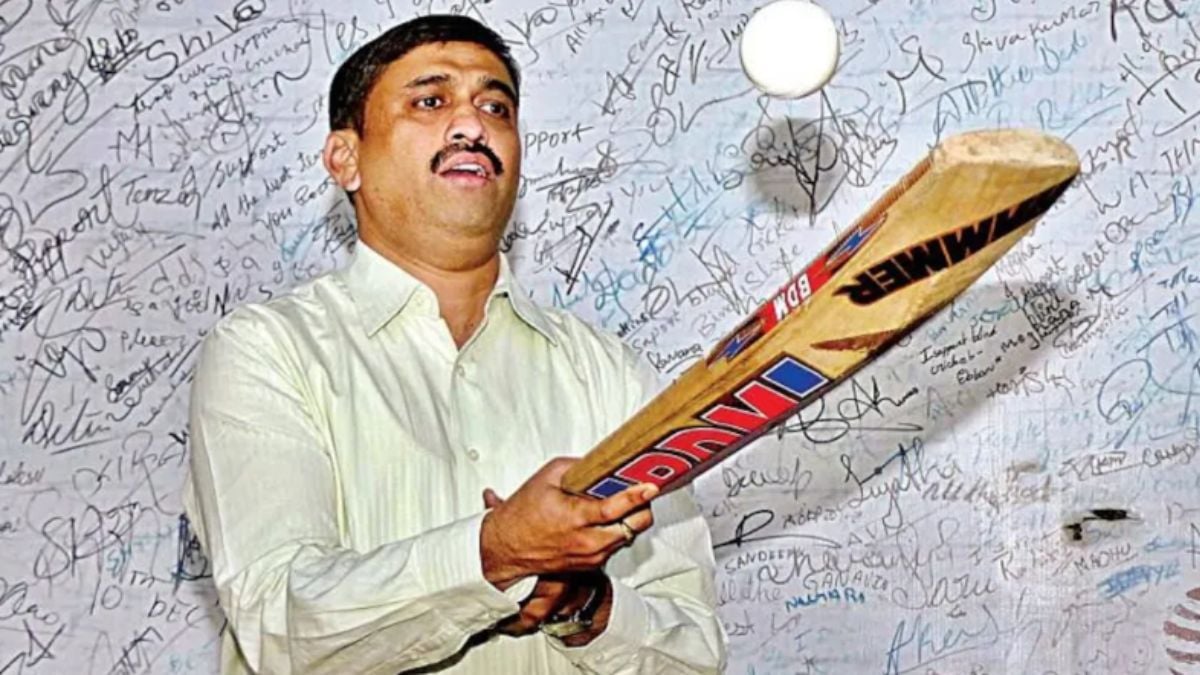

After a decorated career as a player himself, today Mahantesh is a stalwart of the blind cricket administrative set-up in India. Under the aegis of his organization Cricket Association for the Blind in India (CABI), he has helped elevate the standard of the game in India and has nurtured talent in Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and Nepal. Next on his radar is the popularization of the sport in the United States.

On the back of a whirlwind ten-city tour of the United States with the Indian blind cricket team, Mahantesh chatted with India Currents Community Reporter Tanay Gokhale about his efforts to develop talent at the grassroots level across the world, and the sport’s possible inclusion in the 2028 Los Angeles Paralympic Games.

Read excerpts below.

Mahantesh (M): Growing up, my uncle was very interested in cricket. In the neighborhood, he and others used to listen to the cricket commentary through the radio. The way the commentators modulated their voices was very exciting to me. Without knowing anything about it, I just used to sit and imitate that: Four runs! Boundary! and so on.

At the same time, my friends used to play cricket, so they taught me how to hold a bat, how to hit it, how to bowl overarm. They understood my difficulty while batting, so they used to roll the ball along the ground – exactly like they do in professional blind cricket – so that the ball would make a small noise. And after I hit the ball, someone else used to run for me.

Then, when my parents wanted me to attend blind school, my condition was that I would switch schools only if my father bought me some cricket gear so that I could play! My parents have always been supportive and they got me the gear I wanted, and I started playing cricket in the blind school. We also had some teachers who would join us, and they would teach us how to play, modifying the game for us. And when this special cricket ball for the visually impaired was developed in 1988, that was truly life-changing for us.

M: That was the beginning of the cricket journey for a lot of us. Before the ball, there was no formal blind cricket in India. Actually, different countries were playing with different balls – in England, they played with a ball that was slightly smaller than a football, Australians played with a ball made out of tin caps and bottle caps that was threaded together.

In India, after the invention of the ball in 1988, there was some sort of formalization of the game, and we helped organizers build the rules and regulations. Then the first national tournament for blind cricket was held in 1990 in Delhi. In 1996, Delhi hosted an international conference where all the cricket-playing nations came together to establish the World Blind Cricket Council (WBCC), and the Indian ball was decided as the standard ball that would be used all over the world.

M: It is a very nostalgic memory for me. I remember it was during peak winter in Delhi with bare minimum facilities; we slept in a tin shed on the premises of the cricket ground, and there was no hot water! But the level of interest and excitement was high because this was the first time ever that such a tournament was taking place, and there were 25 teams from all over India – it was like a fair!

We played matches all over Delhi, and it was truly well-organized. Kapil Dev was the chief guest actually, and we were able to meet him. If you met a god, how would you feel? That was how it felt. He was our hero who used to bat and bowl, and had won the World Cup in 1983!

Rajiv Gandhi also came for the finals. My team lost in the semi-finals but we were all able to meet him. And because we were visually impaired, we couldn’t see him, so we had to go and feel him. He had no issues. He was a very very warm person, and so when he was killed, at least for a week, it was very hard for me to accept. It was like a dark spot…

But anyway, memories from that first national tournament were the best, even though we had many after that, and then we had World Cups too. Very fond memories!

M: The first major modification is that the ball is different. It’s an audio ball made of fiber plastic, and there are ball bearings inside. Bowling is underarm, and the bearings inside it make a noise as it moves towards the batter. We want the batter to be able to pick up the sound of the ball so the rule is that the first bounce of the ball has to be before the midway mark on the pitch. Another difference is that the stumps or the wicket is made of metal, so that the players can differentiate between the noise of the ball hitting the bat and the ball hitting the wicket. The rest of the equipment like pads, and gloves are the same as cricket.

As for the team composition, players are classified into three categories of blindness: B1 refers to players who are completely blind and who can’t see at all; B2 refers to players who can see up to two or three meters; and B3 players can see up to six meters. Of the eleven players in a team, a minimum of four should be B1, a minimum of three should be B2; and a maximum of four can be B3. B2 and B3 players usually do the running for B1 players and they also field closer to the boundary lines while B1 players are stationed closer to the pitch.

Some of the other rules concerning bowling quotas, batting orders, and the scoring system are also modified to level the playing field between the three categories of players as B1 players are clearly more disadvantaged than the B2 and B3 players.

M: Overall, communication is very, very important because the majority of the training and play depends on auditory signals. First we need to orient the players to the fielding positions on the field like cover, point, gully, long off, and so on. What we do is, we draw a circle of the ground and a pitch using Braille, so they get to feel what the ground looks like. And once they go to the ground, they are taught their positions.

Then during the game, the wicketkeeper has to guide the players to make sure that they are in the correct positions, and that they are throwing the ball to the right and after collecting it. It takes some time for the players to get accustomed to all this but eventually, they become familiar with it.

M: Ever since we (Cricket Association for the Blind in India, or CABI) took over the management of blind cricket in India in 2010-11, we committed to improve the standards, improve their facilities, gear, and focus on their fitness.

What we also strategically did is not to keep blind cricket isolated and segregated but try to mainstream it. Yes, we can’t play with the regular cricketers in a competitive game, but at least we can have matches with them. And they all love the experience of trying to play our game, using our ball. The likes of Rahul Dravid, Virat Kohli, Gautam Gambhir, and Mohammed Kaif have endorsed and supported our cause over the years.

Through cricket, we have communicated the positive side of disability, the positive side of blindness, that if the opportunities are given, they can also play, they can also perform. They can win laurels for the country and make the country proud.

This year, the ex-captain of the Indian blind cricket team Ajay Kumar Reddy received the Arjuna Award, and earlier, another former captain Shekhar Naik received the Padma Shri. All the Presidents from Pranab Mukherjee to Draupadi Murmu have met the teams, and the Prime Minister has also personally felicitated them twice. So taking the game to places like Rashtrapati Bhavan and the PM’s house makes a difference.

Even outside of India, we have tried to support blind cricketers in countries like Nepal, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

M: First off, credit for our U.S. tour goes to entrepreneur Subbu Kota, whose dream was that the Indian blind cricket team should visit the U.S. Through his Kota Foundation, he sponsored our trip to the U.S.

We had multiple objectives for our trip. The first was to promote blind cricket among cricket lovers in the U.S. and the second was to form a men’s and women’s blind cricket team in the U.S. For example, during our U.S. tour, we met a girl called Abigail – or Abby for short – from Wisconsin, during our trip. She was so fascinated with blind cricket that she took a trip to India with her brother in October and spent a month with us, learning the game. Now her mission is to take this all over the U.S. We have started talking to blind schools and finding ways to get youth like Abby trained, because cricket is so new to the U.S. that we want to spread awareness.

Q. And another objective was regarding the 2028 Los Angeles Paralympic Games?

M: Yes, the third objective was to advocate for the inclusion of blind cricket in the Los Angeles Paralympics in 2028, and we have made some noise on that front.

We are writing to the International Paralympic Committee and also the Olympic Organizing Committee in Los Angeles. We haven’t heard anything yet, but we are writing to everyone we can, and hopefully, they will consider our request!

To know more about blind cricket in India and to support its cause, visit .