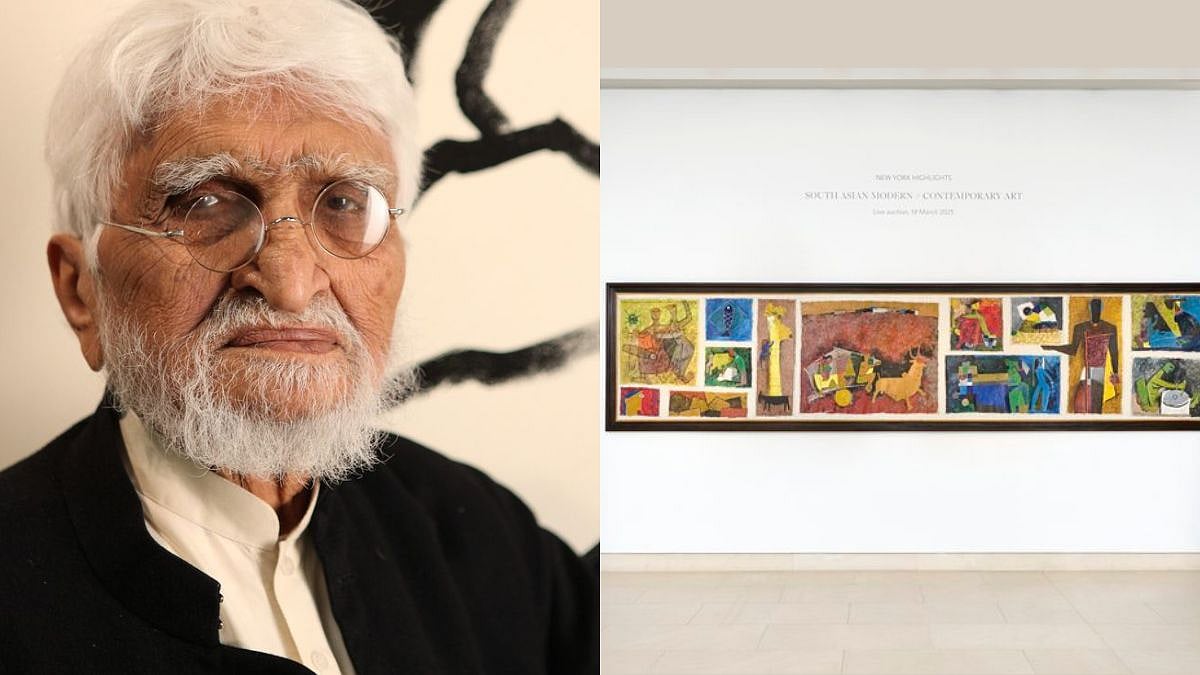

Maqbool Fida Husain: Loving The Art, Disowning The Artist | Pinterest and X (@ChristiesInc)

Maqbool Fida Husain, the painter and filmmaker that India has all but disowned, certainly invisibilised in the last decade, is back at the top of news headlines. As always, it is for the eye-popping amounts that his work continues to fetch on the international circuit and the appreciation that follows for his trademark modified Cubist-style work with bold strokes, vibrant colours, and emblematic figures. This week, at a Christie’s auction in New York, Husain’s untitled painting referred to as ‘Gram Yatra’ was sold for a record-breaking US $13.7 million (approximately Rs 118 crore), making it the most expensive work of modern Indian art sold at a public auction. The earlier record for a Husain canvas was $3.1 million. The successful bid for ‘Gram Yatra’ also broke the record for an Indian work of art, which was Amrita Sher-Gil’s painting ‘The Story Teller’, sold two years ago for $7.1 million.

If there’s pride and pleasure at what the ‘Gram Yatra’, his work from the 1950s, has brought to Husain’s memory and India, it has been muted. The extravagant amount it fetched, many have argued, augurs well for the Indian art market, but there’s little acclaim and adoration for the artist himself. This is both a sad turn of events and a commentary on the polarisation of our times that one of India’s best-known artists on the international circuit is not someone the nation owns or embraces. Husain’s place in the pantheon of creative travellers, who took Indian art and music to international arenas, is no less in art than that of, say, Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Zakir Hussain in music. Yet, the Pandharpur-born and Indore-bred Husain, who spoke fluent Marathi and Hindi, wore Indian attire, relished Indian food, cherished his Padma Vibhushan, and drew deep from India’s visual culture and mythological legacy for his work, evokes little admiration these days. He died a broken man in a London hospital in 2011.

Husain, a common figure in Mumbai’s art precincts, had self-exiled himself five years earlier after a series of controversies erupted over his depiction of Indian goddesses and Bharatmata in his trademark style that turned them seemingly nude. A host of cases were filed in courts across India, vandalism against his work occured, and death threats followed. In those dark times, Husain received support privately from his friends, artists, and intellectuals, but few came out strongly in his favour in the public domain. The controversial series somehow came to define and be the sole exemplar of his large oeuvre of art spanning more than five decades. This is the unfortunate aspect of it all. One of India’s greatest artists was reduced to a few of his controversial frames, and the rest of his life was determined by the public reaction to them. India has all but disowned one of her best.