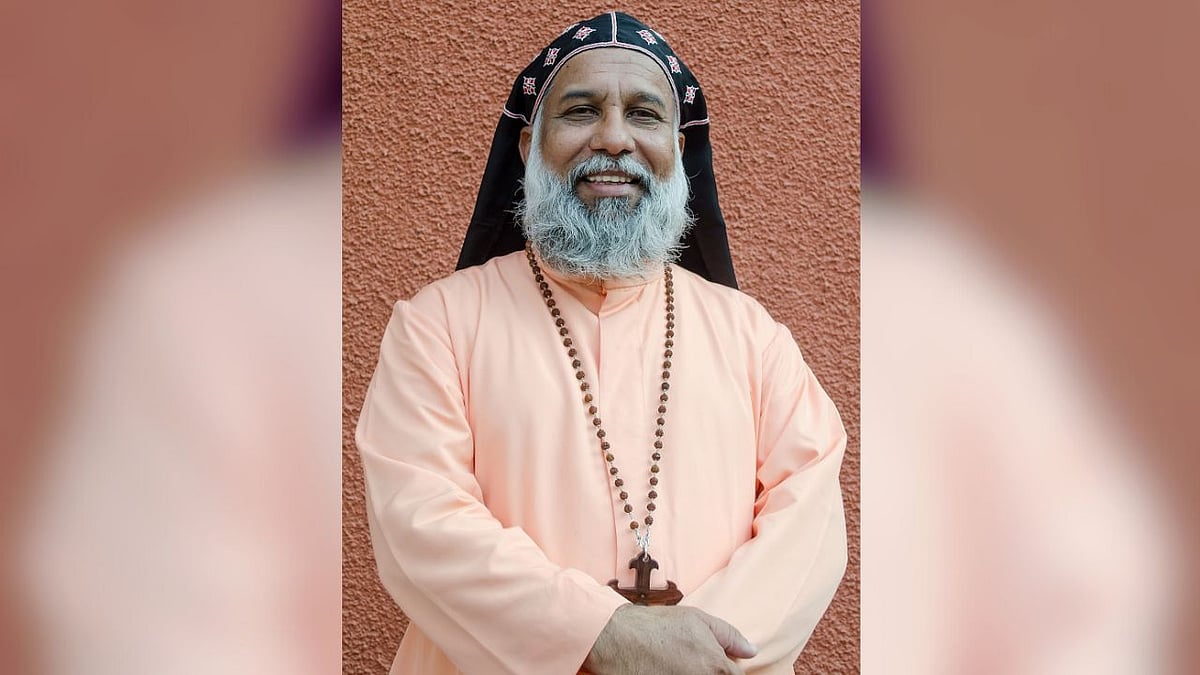

Cardinal Baselios Cleemis of the Kerala Catholic Bishops Council (KCBC) has stirred controversy by urging Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF) MPs to support the Wakf Bill. His statement, coming ahead of the Bill’s presentation, raises serious questions about the role of religious leaders in political decision-making. For one, the exact contents of the Bill remain unknown to the public, as it was vetted by a parliamentary committee. If he had access to the Bill’s provisions before they were officially disclosed, it would constitute a breach of parliamentary privilege. This alone should make lawmakers wary of heeding his advice. It is telling that the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI) has echoed the KCBC stance. This signals institutional support for a government move without even knowing its full implications. The church’s endorsement of the Bill, without proper scrutiny, is both perplexing and alarming.

A cardinal, no matter how influential, has no right to dictate how elected representatives should vote. MPs are accountable to their constituents, not to religious authorities. When the draft Bill was introduced last year, it was opposed by both the UDF and the Left Democratic Front (LDF). Why should their stance change now, simply because a religious leader demands it? In Kerala, where the Muslim community largely supports the UDF, any shift in the Congress’ position on the Wakf Bill could cost it dearly in future elections. The Wakf Board’s control over properties is a sensitive issue, and the perception that the government is interfering in religious endowments has already caused widespread unease. If the UDF parties bow to the church pressure, they risk alienating a crucial segment of their voter base. Cleemis’ pro-BJP leanings have been evident for some time. He recently accepted an award, along with a substantial cash prize, from a Sangh Parivar-affiliated organisation. His justification for supporting the Bill—that a Wakf Board claim on a piece of land is affecting Christian residents—is a weak argument. Such disputes can be resolved through legal means or dialogue rather than political manoeuvring.

It is also alarming that a section of the Catholic Church in Kerala has succumbed to Islamophobia, perpetuating unverified claims about “Love Jihad”. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, bishops continue to raise the issue, deepening communal divides. Similarly, some have linked their political preferences to economic incentives, such as increased rubber prices, sending a troubling message about the church’s role in governance. Religious institutions should refrain from direct political interventions. What is convenient today—supporting government interference in Wakf properties—could set a precedent that may be used against church-owned lands and institutions in the future. By wading into politics, the church risks not only its credibility but also the very autonomy it seeks to protect.