The 2025 Delhi assembly elections are of special significance, given that the future of the Aam Aadmi Party, a unique experiment in democratic politics, is at stake. The question is whether, in public perception, the party has lived up to its promise of alternative politics based on transparency, accountability and swarajya.

AAP is not the first party to have sprung from a social movement for political change, the Nav Nirman Andolan of 1973 is a case in point, but it was the first to have technological tools at its disposal. Digital engagement and social networks were a critical determinant in AAP’s initial success and growth. It was able to create a solid and sustainable organisation, leveraging technology for political mobilisation.

From the start, AAP positioned itself in contrast to established political parties by foregrounding participatory decision-making. To cite the party’s 2014 manifesto: “We believe that decision-making power resides with the people and should be exercised directly by them. In our vision of Swaraj, every citizen of India would be able to participate in decisions that affect their lives.” The overarching message was that ‘the people’ could no longer be taken for granted.

AAP’s revolutionary aspect inspired the educated middle-class youth; even NRI volunteers joined its cadres. In the words of founder-member Yogendra Yadav, it promised to connect politics “to grassroots issues, struggles and movements.” From the moment Kejriwal & Co. crossed the boundary between activism and electoral politics, expectations ran sky-high.

The people oriented and principled stance appealed to the electorate. AAP displaced the Congress in Delhi and wrested four Lok Sabha seats in Punjab the subsequent year. The BJP, with its committed voter base, more or less retained its vote share in Delhi. But the Congress was decimated in Delhi and lost ground in Punjab. In 2022, AAP went on to wrest Punjab from the grand old party and take a large bite out of its vote share in Gujarat. Political analysts speculated on its capacity to replace the Congress nationally as the party of the centre.

AAP triumphed over the BJP in two consecutive assembly elections and evolved the ‘Delhi model’ of governance, privileging education and healthcare in the budget and heavily subsidising utilities for the common citizen as a counter to the development-oriented ‘Gujarat model.’

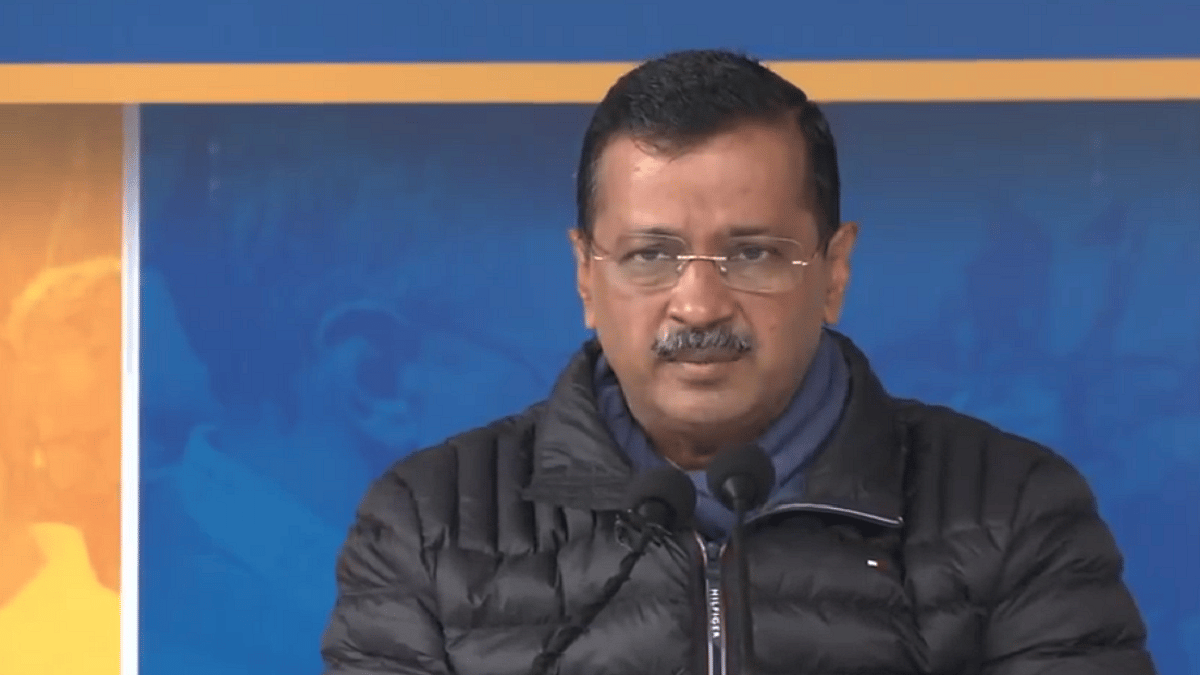

Even as it made electoral gains, internal contradictions plagued the party. Early on, it witnessed a virtual purge of founder members, who disagreed with then chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, notably Yadav and Prashant Bhushan. A personality cult was built up around Kejriwal, who was celebrated as ‘the muffler man,’ an anti-institutional icon. Unilateral decision-making became the norm. Tickets were given to questionable candidates, and crores in public money were spent on party propaganda, legal fees, and, as per the Shunglu Committee report, on irregular appointments and unauthorised overseas tours. Over the years, other members of the inner circle, like former minister Kailash Gahlot, journalist Ashutosh and poet Kumar Vishwas fell out with Kejriwal.

The idea of a participatory approach to policy-making, involving the membership base so as to stay connected to the aam aadmi, found expression in ‘janta ka budget,’ ‘mohalla sabhas’ and ‘school management committee sabhas,’ but only the latter proved to be sustainable. It became increasingly clear that AAP’s hold on power was directly linked to freebies, like free bus travel for women, medication, electricity and water, and to policies like the regularisation of unauthorised colonies.

By the end of Kejriwal’s second term, Delhi’s middle class was disenchanted with AAP’s failure to deliver. Paranoia and a sense of victimhood informed the Delhi government’s dealings with the Centre, resulting in endless confrontations. Meanwhile, public issues, like air pollution, deteriorating water quality, pot-holed roads, mountains of garbage, disappearing green areas and encroachment on public spaces were not addressed. Whether it was the pandemic, dirty water from taps, or the 2020 riots in North-East Delhi, AAP sought to pass the buck to the Centre.

The liquor scam of 2021-22 finally brought AAP down from the moral high ground. The party is alleged to have received kickbacks from liquor vendors, which helped fund the Punjab elections. The very fact that the courts did not prefer bail to jail fostered a feeling that there might be some truth in the allegations. To add to AAP’s woes, the CAG revealed that Rs 33 crore in taxpayer’s money had been spent on renovating Kejriwal’s official residence. TV footage of the ‘sheesh mahal’ further eroded his ‘aam aadmi’ image.

Problems have surfaced in Punjab, with CM Bhagwant Mann reported to be uncomfortable with interference by the ‘high command’ in Delhi. The latter had a say in the allocation of Rajya Sabha seats from Punjab, deployed state transport, and ousted Mann’s confidantes from the CMO and the state Cabinet.

Now, battered by charges of corruption and abuse of public funds, AAP’s very survival is at stake. The Congress has put up a good fight under Sandeep Dikshit, who played the nostalgia card by reminding people of the late Sheila Dikshit’s creditable 15-year term (1998-2013). A Congress revival will work to the advantage of the BJP, which has put up its strongest fight in 27 years by mobilising the RSS cadres. The satta bazaar gives AAP a narrow victory. Win or lose, AAP would do well to recall the principles on which it was founded.

Much sewage has flowed down the Yamuna since AAP exploded on the political scene in 2013. It may have defaulted on its promise to clean up Delhi’s iconic river, but it can clean up its act.

Bhavdeep Kang is a senior journalist with 35 years of experience in working with major newspapers and magazines. She is now an independent writer and author