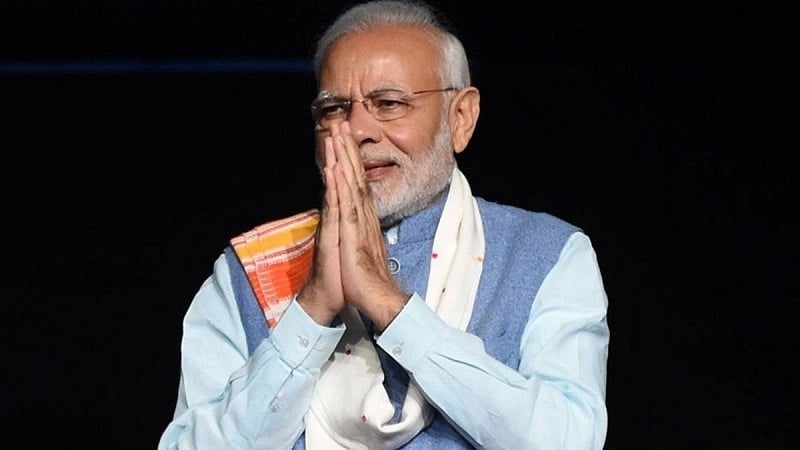

Viksit Bharat represents the government’s vision to transform the country into a developed nation by 2047. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has successfully weaved a popular narrative that India will achieve a developed country status over the next 22 years. But the question is, can India become a developed economy by the mid-century? And how, given its limited public resources and a large section of the population still living in poverty? The government’s infrastructure push has been at the centre of its Viksit Bharat story, but the question is whether building highways, bridges, ports, railways, and airports alone will deliver equitable and sustainable growth in the long run.

Over the past 10 years, the government has confidently projected a bullish outlook for the economy with repeated claims of India emerging as an economic giant. Recently, Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar, at an event in Samastipur district in Bihar, asserted that the country has witnessed “unparalleled” growth in the last decade, causing people’s aspirations to soar. “Viksit Bharat is not a pipedream; it is a goal. It will be realised by 2047 or even before that,” Dhankhar said. Lately, the Prime Minister, too, confidently projected that India’s economy will surpass $10 trillion mark in a decade. Realistic or illusionary?

With many structural problems plaguing the economy, like high unemployment, low wages, lack of skilled workforce, abysmal standards of education and healthcare systems, the rupee collapsing against the dollar, and economic gains disproportionately concentrated amongst a privileged few while vast sections of the population grapple with deepening inequality and limited opportunities, the Modi government’s 10-trillion-dollar goal in 10 years seems an illusory bubble, and the developed economy status by 2047 sounds like a rhetoric. This is not to say that India will not be vastly different from what it is today in socio-economic terms, but to say that it will be a developed economy is an exaggerated claim.

The problem with Modi and his party’s obsession with GDP growth is that they are often comparing India with small countries like the United Kingdom, France and Germany, which are developed nations with less than 10 crore population and a declining workforce. Leaving behind these nations in terms of the size of the economy was a given for a country like India with a 140 billion population. But on various other social and economic parameters, including per capita GDP, India is far behind these prosperous countries. For a fair assessment, India should ideally be compared with China, which is roughly the same size as India in terms of population but is an economic giant and way ahead of India on all socio-economic parameters.

In 1980, India and China were of the same economic (GDP) size. From the mid-1980s, China embraced economic reforms and grew rapidly. In 2000, India’s per capita GDP was $1,357, while China’s was $4,450. India’s liberalisation in 1991 opened the doors for faster growth, but our growth rate could not keep pace with that of China. In 1995, China was ranked the sixth largest in terms of GDP, and 15 years later, in 2010, it attained its place as the second largest. At present, India is the fifth largest in terms of GDP, and it is projected to be the third largest before 2030.

India is at an inflection point where it can propel itself to high growth for a few decades to somewhat emulate China, which had an average growth of 10 percent per annum between 1980 and 2014. According to economic experts, if India grows by 6 percent per annum for the next 23 years, it will manage to achieve a GDP of $13 trillion; at 7 percent, the GDP would touch $15 trillion; with an 8 percent annual growth rate, the GDP could touch $23.3 trillion. But to achieve a GDP of $30 trillion by 2047, the required annual GDP growth rate is around 9.2 percent, a tall order that will need transformative ideas and reforms. But the real question is: should we be fine with GDP as a metric of measurement that does not guarantee equal opportunity to all citizens in education, healthcare, employment, and wage growth?

Physical and social infrastructure developments are crucial for economic prosperity. Both are critical for national development, but a disproportionate focus on one creates an imbalance between the two, which undermines equitable and sustainable growth. To address the deficit in physical infrastructure, the government has initiated ambitious programmes, like the National Infrastructure Pipeline, with an aim to invest Rs 111 lakh crore between 2020 and 2025. This includes substantial allocation for transportation, energy, and water sanitation. However, every year, the government prioritises physical infrastructure over social infrastructure, which is directly linked to human development.

In the 2023-24 Union budget, Rs 11.1 lakh crore was allocated for capital expenditure, primarily for infrastructure. But healthcare and education were given a far smaller allocation of Rs 89,115 crore and Rs 1.12 lakh crore, respectively. This year, the story is not much different. In the Union budget for 2024-25 presented last week, Rs 10.18 lakh crore has been allocated for capital expenditure, reinforcing the government’s commitment to infrastructure-driven growth, while healthcare and education have been allocated Rs 99,858 crore and 1.28 lakh crore. The emphasis on infrastructure, though essential for the GDP growth, comes at the cost of investments in the social sector, which is also essential for development in human well-being.

India’s low HDI ranking at 134 out of 193 countries calls for higher public spending on education, healthcare and social welfare. However, our public spending on education and healthcare hovers around 3 percent of the GDP, which is lower than the global average of 6 percent. The New Education Policy proposed that public spending on education should reach 6 percent of the GDP, but we are stuck with 3 percent, which is reflected in poor learning outcomes. Healthcare fares no better, with severe inadequacies in the healthcare system. Moreover, national schemes designed to address food security, rural employment (MNREGA) and affordable housing continue to remain underfunded.

Ignoring the social sector while prioritising infrastructure will create a shaky foundation for growth. A country where nearly 10 percent of the population is below the international poverty line of $2.15 per day and a large population that is poor, undernourished, poorly educated, under-skilled and unhealthy, cannot harness the benefits of advanced infrastructure. Viksit Bharat needs a holistic approach that links the push for physical development with investments in human development – adequate access to education, healthcare, skill training, and higher wages for all citizens.

The writer is a senior independent Mumbai-based journalist. He tweets at @ali_chougule