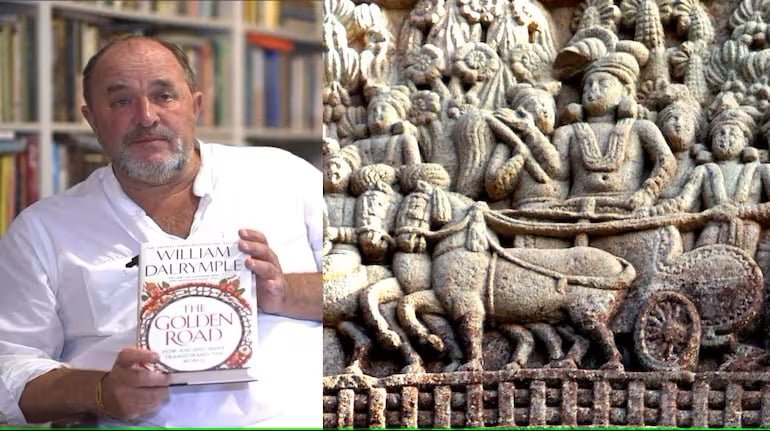

Popular Vs Academic: Shouldering The Burden Of Interpreting The Past | File Photo

The debates sparked by author William Dalrymple’s remarks — where he attributed the prevalence of a distorted and misrepresented history of India, disseminated through platforms like WhatsApp, to the inaccessibility of Indian academic historians — have initiated a crucial discourse on how historical knowledge is produced, taught, and consumed. Dalrymple’s sweeping judgment has been criticised on multiple fronts by historians.

Historian Samyak Ghosh, in his critique of Dalrymple’s statement, argues that academic historians have not failed to reach the “public” but are obstructed by structural and systemic factors. These factors, he contends, are manifestations of Foucauldian power dynamics. Early historical pedagogy and a neoliberal socio-cultural disdain for fields perceived as neither “necessary” nor “useful” exacerbate this issue. Moreover, Ghosh points out that authors of intellectually dishonest historical works are often elevated by popular platforms, reinforcing contentious, ideologically biased narratives.

Journalist Ravish Kumar encapsulates this phenomenon under the term “WhatsApp University”, linking it to the pervasive but rarely discussed issue of “knowledge inequality” in India. Kumar highlights the systemic vacuum created by the political class’s neglect of educational institutions, leaving students — particularly in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities and villages — starved for knowledge. For these students, WhatsApp University becomes a substitute, albeit one riddled with misinformation. This disparity not only affects the quality of education but also undermines critical thinking and cognitive growth.

Dalrymple attributes the rise of such platforms to the failure of Indian academic historians, from the 1950s to the early 2000s, to engage broader audiences, accusing them of insular discourse. However, this argument is flawed on two counts. First, it disregards the contributions of popular historians who have reached diverse audiences. Second, it misplaces blame for misinformation on academics, ignoring the role of the well-organised right-wing nationalist ecosphere, which actively produces and propagates such distorted narratives.

History, as Dalrymple himself acknowledges, is always “by someone, for someone.” It is written by specific authors with their biases and intentions, targeting particular audiences, whether academic specialists or broader groups interested in religion, politics, or national identity. Today, the ruling regime has weaponised history as a tool for ideological control, employing methods such as revising textbooks, distorting debates, and disseminating selective narratives through mainstream media and digital platforms. The resultant hegemony of biased historical interpretations is so deeply entrenched that readers often reject alternative perspectives, even when confronted with factual evidence.

The solution lies not only in improving the teaching of history but also in introducing historiography — the theory and philosophy of history and its writing — at the school level. Such an approach would foster critical thinking and equip students to discern between competing historical narratives.

Within this context, Dalrymple’s latest book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World, exemplifies how history can be crafted to appeal to nationalist audiences. By showcasing India’s influence through trade, religion, and culture on regions from Southeast Asia to Europe, the book taps into a marketable narrative that resonates with its audience. This does not detract from the work’s scholarly merits, which rest on solid research, but it underscores the need for readers to approach such works critically.

Ultimately, we must question who writes history, for what purpose, and for which audience. Only by engaging with both popular and academic histories critically can we achieve a balanced understanding of the past and its implications for the present.

Conrad Kunal Barwa is a senior research analyst at a private think tank and a senior research associate at the Birmingham Business School. Abhinandan Pandey is a postgraduate researcher in history and a published Urdu poet.